1968 – Summer of Chaos

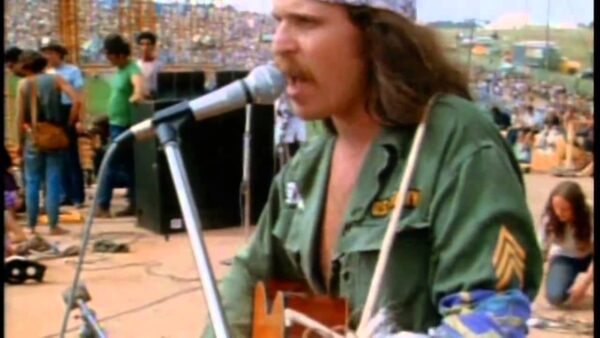

“Come on all of you big strong men. Uncle Sam needs your help again. He’s got himself in a terrible jam. Way down yonder in Viet Nam so. Put down your books and pick up a gun we’re. Gonna have a whole lotta fun” — “Country” Joe McDonald from Fix’n to Die Rag

Country Joe McDonald is a neighbor of mine who came back home to Berkeley in the early 60’s from 3 years in the Navy — disillusioned and angry, but with a still fully functioning moral compass and a soul full of music ready to emerge. Joining the LSD scene just after the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane began their musical/metaphysical explorations, Country Joe and the Fish became a mainstay at the early acid tests, and while he and his band produced some of the finest psychedelic music of the era, most people associate him with the band’s iconic “Fix’n to Die Rag” – a song that helped end the Vietnam War.

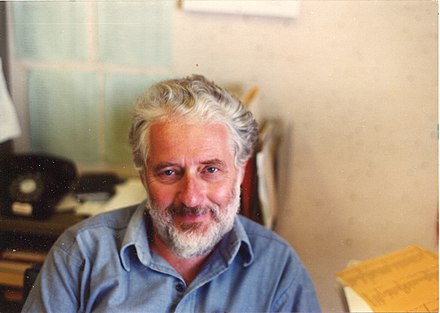

Moe Hirsch

I never met Country Joe, but I did get to know Moe Hirsch, one of the many musicians who sat in with him at his informal jam sessions at the Jabberwock Coffee House on Telegraph Ave just south of the campus. Moe, a brilliant radical left-wing mathematician as well as a skilled and versatile musician, bonded with Joe over politics and musical sensibility. He and Charity, his equally brilliant wife, were part of what I came back to Berkeley for.

In 1960 when we first moved to Berkeley, Moe was consumed with his academic career, blazing a trail at the UC Berkeley Math Department in Topology, one of the most remote and inaccessible regions of mathematical abstraction. Along with several other great mathematicians in the Bay area, Moe also spent time exploring the world of mathematical Chaos. Unlike my father, Moe recognized Chaos as a brand new way of looking at how reality moves through time and ultimately wrote a textbook on the subject. My father was also a topologist, but his interest was in Knot Theory – how one, two, and three-dimensional objects (curves, surfaces, and solids) can be twisted, transformed and embedded in higher dimensional spaces. My father was interested in what is — how things that look different can actually be the same, but not how things might change over time. Yet despite these differences, both Moe and my father used the same topological lens to search for Truth in the abstractions of higher math. Soon he and Moe had become close friends, sharing their love of higher mathematics as well as an appreciation for beatnik culture, political satire and Dixieland Jazz.

By 1968 when we returned to Northern California, Moe and my father had travelled a long way down radically different paths and were inhabiting two different versions of reality. Moe had become a tenured professor, establishing himself not only as a leading topologist but also as one of the leading proponents of Chaos theory. At that time, however, he was much more passionate about politics than math, trying to stop the Vietnam War and becoming one of the first professors to actively support the student strikes and protest marches. He fully participated, speaking out loudly and eloquently against the US Government and its conduct of the War. He took advantage of his “untouchable” status as a tenured professor to act and say things that could have gotten an ordinary academic fired or at least thrown off the “tenure track”. Beyond his political activities, Moe was also playing a lot of music. Along with Country Joe and many others, he contributed to the soundtrack of the movement that eventually ended the War.

My father, on the other hand, had become a Cold Warrior.

My father, on the other hand, had become a Cold Warrior.

Recruited by the National Security Agency (“NSA”) he set aside other career ambitions and joined a top-secret group of mathematicians doing research on some very specific problems, the solutions of which could be shown only to a select group of NSA officers and Defense Department officials with the very highest security clearance. They hid their work in plain sight, working in a non-descript brick building set amongst a group of similar structures tucked away in an obscure corner of Princeton University’s bucolic green and ivy tinged campus. The building was called “Von Neuman Hall” and those who did some digging in the public records would find that the sole tenant of the building was anorganization called “IDA-CRD”. The letters stood for “Institute for Defense Analyses – Communications Research Division” but not many people besides those who worked there knew that or considered what the name suggested the organization’s mission might be. Few noticed the building and even fewer tried to discover what was going on inside. In fact, behind those brick walls sat one of the most powerful computers in the world tended by 40 of the most powerful mathematical minds in the country pouring all their energy into trying to decode the secret messages of our enemies around the globe.

My father was excited and proud to be doing what he felt was vitally important work defending his country; a country that he loved deeply and considered the greatest and freest on earth. He thrived in the environment. He was good at keeping secrets, was a talented mathematician who enjoyed collaboration and he appreciated the “no bullshit” attitude of the NSA culture as well as their ability to create a completely secure but ideal environment at IDA for brilliant (and often eccentric) intellects to convene and jointly solve difficult problems. Eventually my father got promoted to Deputy Director of the group and soon he was traveling to Fort Meade in Maryland to make periodic reports to the higher-ups at the NSA. He was happy and we were proud of him. We knew he had an important job even though he could never tell anyone, not even his family, what he did all day.

But by 1968 things were getting complicated.

The Summer of Love was over and the country was beginning to fracture. Protests against the Vietnam War were beginning to get more serious and anger between the generations was boiling over.

I was largely oblivious, being an 11 year-old boy more interested in sports, science fiction and comic books. I spent my days trading baseball cards with my friends at school, considering whether the Legion of Super Heroes could really exist, and fantasizing about travelling to other planets when I grew up. We lived in a rural area several miles outside of Princeton and I went to a pure white private country day school just up the road. My parents protected me — not only from the reality of what my father did for a living, but also from the cracks that were starting to appear in the Great Society of Lyndon Johnson’s America. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in April, I remember going to school and seeing Dave White, the janitor of our school, sitting outside the kindergarten classroom with his 5 year-old granddaughter, the only Afro-American student in the school. He had his head in his hands and was quietly but visibly crying while his granddaughter sat by his side trying to understand what was happening. It was a shocking scene, but one that I couldn’t process and knew instinctively I should flee from. And so I went on to my 6th grade classroom where no mention was made of the assassination or why Dave was not making his usual rounds through the building.

When RFK was shot in June, I paid more attention.

The race for president was to me a spectator sport, and Robert Kennedy was one of the candidates I was rooting for. He was one of the good guys, and good guys don’t get killed so early in the movie. Something was very wrong with the story I was being told and I started to follow the news more closely. Despite my father’s best efforts at damage control and spin, I began to suspect that I may have mistaken the heroes for the villains and vice versa. Race riots were breaking out in dozens of cities, and the truth of what was happening slowly seeped into my brain through the nightly news which I now watched religiously. I still didn’t understand the rage that was suddenly let loose throughout the country or exactly why we were at war in southeast Asia, but while I felt unaffected personally, my long sleeping conscience was starting to stir.

The town of Princeton was still quiet, peaceful and largely unconcerned with the political unrest sweeping the country, but the students at the University were wide awake, and anti-war noise and protest signs were beginning to pop up throughout the town. The University’s support of IDA was now common knowledge among the anti-war activists on campus and they were not happy. I’m sure my father and his superiors at Fort Meade discussed the situation, but of course, neither I nor anyone close to me knew anything about what they talked about.

Coincidentally or not, my father let us know that in July IDA was going to send a few of the mathematicians and their families (including us) to California for a two-month conference. This was great news and my whole family was excited. We would be spending most of the summer at the Naval Post-Graduate School in the (still) sleepy town of Monterey California, 50 miles south of San Francisco, but would have plenty of time to visit old friends in Berkeley and travel up and down the coast.

The Naval Post Graduate School was the finishing program for elite officers of the Navy.

The Academy itself sits on a manicured campus set near downtown, tastefully surrounded by well-constructed and not too ugly thick high white stucco walls.

We lived just outside of Monterey in the surreally beautiful hamlet of Carmel. I spent my days at the Navy’s swimming pool along with many of the IDA employee wives and children. Sometimes I played chess and ping pong with other mathematician kids or with a friendly officer-in-training who happened to be on a break. On the weekends we would go to the beach or drive down the Coast Highway which began just south of Carmel.

And then there were the parties. Both at our house and in Berkeley, my sister and I got to be spectators at eclectic gatherings of mathematicians who, despite popular conceptions, comprised a highly social culture. It wasn’t just the codebreakers at these events. With Berkeley and Stanford within easy driving distance of Monterey, at least one of the gatherings I attended included mathematicians from those universities as well. Moe, of course, was among the guests.

Against all odds, my father and Moe had stayed close friends. Moe lived in a different world from that of the codebreakers. He might not have known what my father’s conference was all about, but the language of mathematics is universal and Moe, as well as others from the Berkeley and Stanford Math departments, were welcome guests and only distinguishable from the IDA people by their somewhat longer hair and the music that they listened to and/or played. I’m not sure if they ever talked politics, but there was juggling, a lot of music, and more than a little wine. And if both Moe and a piano were present, there would undoubtedly be carousing well into the night.

Moe was exciting and fun to be around. He didn’t interact with my sister and me so much, but he did give me my first two Rock n Roll albums; one by the Beatles and one by the Rolling Stones. I think, in his own gentle way, he was trying to show me that there was an entirely different way of looking at life that you don’t learn at school or from your parents. He planted a seed that would take many years to take root and grow.

When not breaking codes or socializing, my father made sure we got to appreciate the overwhelming natural beauty of Northern California.

Weekends were often spent driving to local State parks or down Route 1 to Big Sur. Though it would be years before I tried cannabis, let alone any other more serious drugs, it was on one of those day trips that I had my first psychedelic experience.

When I go there now, I can feel the magic energy of Big Sur growing stronger almost as soon as I drive past Point Lobos, through the Carmel Highlands and onto the Coast Highway, but as a child in the backseat of the 1967 Chevrolet sedan my father had rented for the trip, the twists and turns of the road were like being trapped on a poorly designed amusement ride – too long, too slow and with only the occasional scary hairpin turn or scenic vista to enjoy, before focusing on holding my pee and fending off carsickness.

Soon enough hunger overwhelmed my nausea and straining bladder. As confident in my parents as I was, I started to panic. Looking out the window, I could see no sign of civilization and the one that said “next gas -32 miles” did not provide much cause for hope. My parents were in their own world; smiling, chatting quietly to each other, occasionally oohing and ahhing at the magnificence around them, and they seemed not the least bit worried – not about us or our suffering. My sister asked me “where are we going and when are we going to get there?” Being her surrogate protector, I pretended everything was ok, and said “soon, don’t worry”.

“Soon” it wasn’t, but a little after 2pm, we passed through the tiny town of Big Sur, where we stopped for gas and to pee before continuing on for less than a mile to Nepenthe, the most spectacularly located hamburger joint in America, and possibly the world. My father hates waiting in lines and he had timed our arrival perfectly to beat the lunchtime crowd but with little attention given to the painful gnawing hunger he had generated in his children who were used to a household run with military precision and who acutely felt any slight deviation in the timing of our customary noontime meal.

Reaching the patio dining area at the top of a long set of steps snaking up from the parking lot, we found ourselves on what seemed to be another planet. Or maybe it was the same planet, only we had walked through a crack in the space time continuum and ended up in the same place but in a parallel Universe.

The aromas hit me first.

Grilling burger smoke mixed with the smell of flowering jasmine lining the steps to the terrace and the misting salt air that whirled its way up from the violent collisions of waves crashing into the giant rocks strewn at the base of the sheer 200 foot cliff that started 10 feet beyond the edge of the patio. The combination produced a cloud of vapors that cast a spell on everyone who entered it.

Like the hero in Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon”, I walked toward the Ocean in a dream like state convinced that I had been transported to a real-life Shangri-La. As I got closer to the cliff, the sounds arrived – overlapping muffled roars resolving into individual waves releasing their kinetic energy on the rocks below, each with its own unique pitch, power and duration. I listened mesmerized to my first real “journey music” – The Chaos of the Shoreline, composed by God and playing in an (almost) endless loop at venues across the Planet. Only I was listening to this particular performance in one of the holiest amphitheaters on Earth – a spot to which tourists travel thousands of miles to see, a spot held sacred by the Esalen Indians who first settled the area, and a spot that remains to this day too wild for humans to tame.

I got to the edge of the cliff and looked over the low fence gazing down and to the South. I longed for the telescopic and X-ray vision of my favorite comic book superheroes so I could better see the complex dance of light, water, land and clouds that was taking place below me. I stood transfixed for a long 30 seconds – until I realized just how hungry I was.

Biting into my “Ambrosia Burger” I moved to another level of consciousness. My taste buds exploded around the best hamburger I’ve ever had in my life. Covered in “ambrosia sauce” (mayo, ketchup and some secret seasonings) it was too good to eat quickly. Even though I was a ravenous 11 year-old, I was driven to quietly savor it and simply immerse myself in the paradise that my parents had brought me to.

After lunch we perused the bookstore downstairs and absorbed some of the culture of 1968 Big Sur and the Esalen Institute just a few more miles down the road. While the mathematicians to the North were learning to understand the dance of Chaos that turns the present into the future and the physicists in Southern California were exploring the Quantum Mechanical nature of reality, here in the middle of the State, scientists of the mind were trying to understand consciousness and what it meant to be human.

Big Sur was where all forms of water; the waves from the Ocean, the clouds up above, the river flowing down from the mountains and the volcanic hot springs boiling up from deep underground, meet and mingle at the intersection of land, sea and sky — merging and mixing in a Chaotic dance of their own. And here was where psychologists like Abraham Maslow and Fritz Perls, writer/philosophers like Alan Watts and Aldous Huxley, and psychedelic pioneers like Timothy Leary and Ram Das met to try and figure it all out. I was too young to really understand all of what was happening here, but with my suddenly opened senses, I was able to metabolize at least the gist. It was new, it was change, and it was real. That much I got, and that is what remained dormant within me for almost a decade, before a friendly Deadhead in the Springfield Civic Center parking lot gave me a magic tab that woke me up.

As important as my year in Berkeley was, it was the memories of the Summer of ’68 that consciously drew me back to the Bay area.

When I think about the mathematicians who worked at IDA and those others who I grew up with it occurs to me that the different kinds of mathematics they engaged in can be thought of as looking at reality through a tetrahedral prism with four faces – the view through each diffracting and bending the light in different ways that make the world impossible to understand in total.

There is my father’s type of mathematics that imagines reality as a static extraordinarily complex structure of multi- dimensional objects embedded in even higher dimensional spaces. This is the “Knot Theoretical” view and while there weren’t too many topologists at IDA their perspective on codebreaking was highly valued.

Then there are those who imagine reality in bits and bytes, discrete but almost innumerable possibilities that emerge as result of the even more numerous algorithms that produce all that we observe now and in the future. These mathematicians study the combinations and permutations, mostly of numbers, but sometimes of objects even more abstract. There is nothing uncertain in this mathematical reality. All is deterministic and theoretically discoverable. These are the number and information theorists who, for perhaps obvious reasons, made up the bulk of the mathematicians at IDA.

Finally, there were a few probability theorists at IDA who studied the future as if it were a godless expanse governed by Randomness and Stochastic processes.

Many of these eventually left IDA to apply their secret knowledge to the investment markets and became unreasonably wealthy by understanding deeply how, where and when the uncertain and unpredictable future can be managed to the advantage of those who make the right “bets”.

But there is a fourth kind of mathematics, though none of the mathematicians I knew at IDA practiced it. These mathematicians frame and solve problems based on the premise that reality is more like a non-linear dynamic system of intractable complexity, one where temporary calm waters can turn suddenly into turbulence, one governed by processes that are deterministic, but which, paradoxically, are not predictable because we can never know the initial conditions of the Universe or the precise algorithms that drives its change.

This is the mathematics of Chaos.

It is the face of the prism that scatters the light into an ever-shifting rainbow of colors, and mathematicians like Moe and the handful of others who practice it are a rare breed.

For me, this face of the prism is the psychedelic one. It is the one that inspired Country Joe, the Grateful Dead and all the “journey music” that followed. Country Joe describes the landscape as “the painted desert adrift off of Donovan’s reef” calling on each of us to “open your mind, show me a sign and prove you’re insane.”

But it is also lens that allows access to and honors the magic of human consciousness, the beauty of the endlessly changing but never repeating vistas we find at Big Sur and on our path through life. It is the view which appreciates not just the beauty of the structure of the Universe itself, but also the beauty that Chaos produces all around us. Most importantly it recognizes that we too are an essential part of that Universe – a thread woven into a grand tapestry of infinite exquisite fractal complexity.

I know I’ll never understand the Universe, but I do know which side of the Prism I want to look through while I try.

Actuay and Author Peter Neuwirth, FSA, FCA

About Peter J. Neuwirth FSA, FCA: An actuary specializing in retirement plan issues, Pete is a 1979 graduate of Harvard College with a BA in Mathematics and Linguistics. After leaving Harvard, he went to work at Connecticut General Life Insurance, now CIGNA, and for the next 38 years, he worked continuously as an actuary holding significant leadership positions at a variety of firms around the country, including most of the major consulting firms (Aon, Hewitt Associates, Watson Wyatt, Towers Perrin and finally Towers Watson).

Additionally, he has spent 5 years as a chief actuary at a regional benefits consulting firm (Godwins), 7 years running a small actuarial firm (Coates Kenney), and one year in a large accounting firm (Price Waterhouse). At the end of 2016, he retired from Towers Watson to focus on writing and researching financial wellness issues.

Peter continues researching various financial wellness issues, including using home equity to generate retirement income. In 2018 he taught a graduate seminar on this subject for the actuarial science department at the University of California at Santa Barbara. He is currently associated with the Academy for Home Equity in Financial Planning at the University of Illinois.

In addition to his books “Money Mountaineering” and “What’s Your Future Worth?”, his research has been published in professional journals, including the Journal of Deferred Compensation, Contingencies, and Journal of Financial Planning. His articles have also been published in numerous online actuarial web publications. He is a frequent speaker at professional conferences such as the Conference of Consulting Actuaries, Enrolled Actuaries, and Western Pension and Benefits Conference. He is a Fellow of the Society of Actuaries and the Conference of Consulting Actuaries.

Contact Pete:

- Office: 109 W. 7th Street, Santa Rosa, CA 95401

- Website: peterneuwirth.com

- Email: peteneuwirth@gmail.com

- Call: 707.537.5075