COVID Quarantine and walking through the oldest neighborhood in Santa Rosa

Many consider Railroad Square to be the oldest part of town, but I discovered a neighborhood even older, and that is where I have been spending time while my nasal swab and future health are being analyzed in the County COVID lab. In some ways, I feel like Schrodinger’s Cat – neither dead nor alive until the test results come back, and I know for sure whether or not I have the dread disease. But while I wait, I have been told by my doctor to stay inside as much as I can but get some exercise by walking – making sure I only venture to places where there are no others who I might infect if I am COVID-positive.

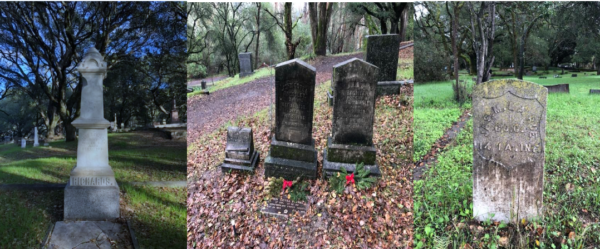

And so I have been spending the last three days exploring the Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery – a graveyard whose entrance is at the end of Carr Ave, just a 3-minute walk from my apartment. The first burial there occurred in 1854, and up until the 1930s, Santa Rosa residents and others in Sonoma County purchased plots and had themselves and their families buried there. It is a fascinating 17 acres piece of land full of old Valley Oaks and many hundreds of lives documented by an extraordinary variety of monuments, markers, and gravestones of wood and stone, almost all of them bearing some sort of farewell message or tribute to the tenant of that particular piece of earth.

I had strolled through the grounds many times on my way to pick up groceries at the Pacific Market, just on the other side of McConnell Avenue, but until my COVID quarantine, I hadn’t spent much time actually getting to know the place and its inhabitants. Two things drew me back to take a closer look at what was there. The first was the circumstances of my confinement, but the second was because of a Christmas story “Grandpa Joe” told me while waiting for Linda to bring out the food and open presents.

I had strolled through the grounds many times on my way to pick up groceries at the Pacific Market, just on the other side of McConnell Avenue, but until my COVID quarantine, I hadn’t spent much time actually getting to know the place and its inhabitants. Two things drew me back to take a closer look at what was there. The first was the circumstances of my confinement, but the second was because of a Christmas story “Grandpa Joe” told me while waiting for Linda to bring out the food and open presents.

When Joe heard where I was living, he said – “Oh, you are right by where the last vigilante hanging in Santa Rosa took place,” and then proceeded to tell me what he knew about the night of December 9, 1920, when a group of Santa Rosa’s “concerned citizens” captured and hung three members of the “Howard Street Gang” who had broken out of a San Francisco jail, killed three law officers and headed north. According to Joe, the vigilantes had strung up the criminals on an Oak tree right at the end of Carr Avenue and buried their bodies in unmarked graves somewhere in the cemetery.

This was a story that I could not let go of, and so beginning on December 30 and through the weekend, I spent my late afternoons (when it is too cold and often rainy for even the most intrepid of graveyard strollers to visit) exploring the space closely — taking pictures of gravestones and anything else there that looked interesting or indicative of what had happened almost exactly 100 years earlier.

Those who know me well also know that once I get started on a project like this, I don’t stop with taking pictures of the subject at hand.

My first goal was to find the hanging tree and learn more about the events themselves. There were two possibilities. Joe had said that the criminals had been hung from an “an oak tree at the edge of the cemetery right where Carr runs into Franklin. When I went there I found these two which both looked like a pretty good candidates.

My first goal was to find the hanging tree and learn more about the events themselves. There were two possibilities. Joe had said that the criminals had been hung from an “an oak tree at the edge of the cemetery right where Carr runs into Franklin. When I went there I found these two which both looked like a pretty good candidates.

Each of the two were in the right spot, and while the one on the right was inside the fence surrounding the graveyard, the one on the left looked older, and more suited to the grim task undertaken 100 years before.

Once I entered the cemetery itself, however, I found a faded information guide directing me to this Locust tree, which the pamphlet said was where the hanging took place.

Since I was only a few blocks from home, I returned to my computer and looked for more documentation. The Historical Society of Santa Rosa account in 2016 discussed how “the exceptionally long branch growing on one side of this rather ordinary black locust tree strained under the weight of three men hanging there with nooses around their necks.”

Facebook posts talked about how the criminals were buried in unmarked graves within the cemetery, that the original locust tree was now gone because souvenir hunters had cut it up and carried most of it away, and that what remained was only what had grown back in the last few decades. There was also a faded picture of the three dead men with their necks broken and their bodies suspended well above the ground. Unfortunately, the tree itself, where they were hung, was not visible in the photo. I was fully prepared to believe that Joe had gotten confused as to the species of the tree, but I also wasn’t convinced that the Historical Society or Facebook was correct about the story either, so I kept digging.

Remembering my father’s lessons about primary sources, I went to see if I could find any “contemporaneous accounts” and was happily surprised to find two newspaper articles written the day after it happened available online. The first was from the December 10, 1920, edition of The Sacramento Union, and the second was from the Madera Tribune of the same date.

Remembering my father’s lessons about primary sources, I went to see if I could find any “contemporaneous accounts” and was happily surprised to find two newspaper articles written the day after it happened available online. The first was from the December 10, 1920, edition of The Sacramento Union, and the second was from the Madera Tribune of the same date.

Both articles clearly stated that the men were hanged from an oak and not a locust tree, as the Historical Society suggested. The Sacramento Union, in particular, was pretty clear, stating: “The three men were taken from the machines (i.e., automobiles) and hanged to an oak tree”

The article has many interesting details about the Howard Street Gang, the criminals themselves, and the mayhem they caused. What was conspicuously absent from the account was any suggestion that what the vigilantes had done was wrong. They were apparently known to be very bad men who had assaulted women and killed three police officers. As far as the newspaper was concerned, justice had been served. If there was any doubt as to where and how the execution took place, the article concluded by portraying the final scene of the spectacle by describing how“….the bodies dangled from the oak tree.”

With the exception of those history buffs who happen to have a collectible piece of wood in their home, it really doesn’t matter whether it was a locust or an oak tree that provided the scaffolding for this 100-year-old drama, but it does illustrate the difficulty in determining what actually happened in the past.

In this case, the species of the tree also has no bearing on the larger moral issues associated with judgment and punishment and how we humans can create and live in a just society, but there are plenty of other stories in the Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery that bear directly on these critical issues that have always been with and probably always will be.

Now I want to talk about two gravestones that bear directly on these difficult and dangerous subjects: John Richards, Colonel Pressley and the “Swamp of Confederate Sympathizers.”

Now I want to talk about two gravestones that bear directly on these difficult and dangerous subjects: John Richards, Colonel Pressley and the “Swamp of Confederate Sympathizers.”