COVID Mortality and the state of the Life Insurance Business

Having been around the Insurance Industry for over 40 years, I have learned a few things about the business model that has kept large carriers alive and profitable for decades and sometimes centuries (several of the big ones have been around since the 19th century).

One of the key principles I have seen in operation is that hazards almost never turn out as bad as policyholders fear – except when they turn out much, much worse. As a result, insurance companies are able to charge premiums that will generate a profit but do need to attend to the possibility of a “black swan event” that could be truly catastrophic. Fundamentally much of insurance is based on the fact that even though we live in a “fat tailed” world where the mean is far greater than the median, most consumers, even the most sophisticated ones, operate as if risks follow a Normal distribution. In a sense this creates a win-win situation where policy holders feel they are getting risk protection at a reasonable price, while the carriers, with their huge cash reserves, underwriting protocols and re-insurance treaties to protect them from catastrophe, continue to make a good profit collecting premiums in excess of claims.

When it comes to this pandemic, we can see this principle at play in real time. COVID-19 is a quintessential black swan, and when it came ashore early last year, I along with many other actuaries, tried to figure out just how bad this scourge was and most importantly, how bad was it going to get. My particular focus was on COVID-19 mortality, in part because it seemed to be the one aspect of the pandemic that was more tractable than the others (i.e., people are either alive or dead) and partly because mortality risk is so central to the health of the Life Insurance Industry which my employer CapAcuity consults about.

It was tricky because data was hard to come by and the disease itself was poorly understood. Nevertheless, in June of last year, I put together an analysis of COVID mortality and published an article on how many people would ultimately die of the disease. My conclusion was that by the time a vaccine was generally available 475,000 people would have died from COVID. The article is available at http://www.peterneuwirth.com/?page_id=632

My conclusion, which I believe has proven correct, was that this disease is terrible, but not quite as terrible as people feared. Most pundits at the time were expecting deaths to be well over a million before the pandemic ended, and while my article was well received, there were many who thought I was being overly optimistic about the future course of the pandemic.

With the pandemic now easing its grip on us and vaccines beginning to be generally available, I thought it was time for a follow up analysis.

An updated analysis of COVID mortality

Late last summer, I had actually begun to look at how my projections were turning out and was somewhat disturbed to find that the CDC data I had relied on was becoming messy and difficult to parse. In particular, beginning with some County health departments in Texas, the definition of what constituted a “COVID-19 death” began to shift from “dying from COVID” to “dying with COVID” (i.e., even if you die from a stress induced heart attack after having contracted the disease you are included in the count). You can read about how and why the change was made at here. I don’t doubt that this change was made with the best of intentions, but unfortunately when you change definitions like this, analysis becomes much more difficult.

The good news is that Life Insurance companies don’t much care why you die, they are just interested in the fact that a claim is now payable. As a result, when I took a fresh look at the data, I focused on the number of “extra deaths” that we have experienced as a result of living (and dying) with the disease. I also talked at length with my colleagues at various life insurance companies to find out how worried they were about any “underwriting apocalypse” that might befall the industry.

It turns out that the CDC continues to keep very good data on total deaths even though the number of “COVID deaths” for reasons noted above is pretty noisy, and in particular very difficult to use to compare the direct impact of the virus in the autumn to that experienced during the early part of the year. To address this challenge, I developed a baseline of “normal deaths” and compared that to what happened in 2020 which differed from prior years due to the presence of the virus in our midst. This effort was complicated because of various factors including population growth and the normal season- ality of mortality (November- March generally being the most lethal months), but in the end, I believe I was able to at least see the big picture of what is going on.

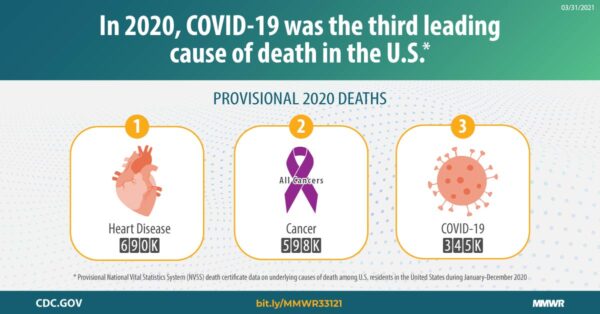

By comparing deaths in 2020 to those in 2017-2019 (adjusting for population changes in the last 4 years), I found that while the number of reported COVID deaths in 2020 was 374,121 (a mix of those dying “from” and those dying “with” the disease) there were 472,116 “excess deaths” relative to what we would actuarially expect during 2020. The difference between these two numbers (97,995) is the number of people who died from the indirect effects of the pandemic. In my June article, I had looked at this and found that in the early days of the pandemic, there were actually less total people dying of non- COVID causes than expected, mostly due to reduced auto accidents and flu deaths. While this was good news, I speculated then that once the effects of deferred medical care and economic hardship began to affect mortality, we could see this trend reverse. It seems that this has happened, andthe important question now is whether these secondary effects will persist or fade away when the pandemic ends. The chart below summarizes these numbers and notes where the data comes from.

374,121 COVID deaths and 472,116 excess deaths are both big numbers, but when we really look at the impact of this increased mortality risk on the Life Insurance industry, we find that the current impact is very mild and no one within the industry whose career depends on it seems particularly worried. I am not sure why this is the case, but my guess is that it is because those that died because of the pandemic had less life insurance than the average American.

That is not to say, that Life Insurance companies are ignoring COVID, but at least within the product lines that I am most familiar with, i.e. Corporate Owned Life Insurance (COLI) and Whole Life Insurance, what I am seeing is modest adjustments in underwriting standards and virtually no changes in the premiums that policyholders are being asked to pay.

Pacific Life is one of the leading issuers of both COLI and Whole Life. In preparation for this article, I spoke with Greg Reber about Pac Life’s view of COVID’s impact. Greg is Pac Life’s Chief Distribu- tion Officer in charge of the distribution of all the life insurance products that the company issues, and as a result has a bird’s eye view of how at least one big insurance company views the situation.

Greg told me that for him, and for Pac Life, underwriting issues around COVID mortality are far less a concern than the continued low interest rate environment and the potential for Corporate income tax rates to increase substantially under the new Democratic administration. He thought that both of these macroeconomic factors posed greater challenges and opportunities for the industry than the prospect of many more COVID deaths. That being said, Greg explained that the Company was responding to all three of those aspects of the current environment.

With respect to the two economic issues, Greg was quite optimistic about the future of COLI. With higher tax rates, COLI will become a much more tax efficient corporate financing vehicle for numerous purposes, and while chronically low interest rates make “fixed” products perform worse, Pac Life was responding by shifting resources toward their “variable” products where recent stock market performance has made those products particularly attractive.

With respect to COVID specifically, Greg said that claims had not materially increased during the pandemic, perhaps due to the sad fact that many of those who have died from the disease had limited or no life insurance. In any event, Pac Life’s COLI business has not suffered at all, though Greg said that they were taking certain steps to guard against potential “antiselection” and other factors that may impact profitability if COVID surges again. Specifically, Greg said that the company was deemphasizing its corporate sponsored products (i.e., life insurance that employees choose to obtain with subsidies from the company) and focusing more on its corporate owned products (COLI, corporate owned annuities, and life insurance for groups of executives).

As I noted at the beginning, actuaries have a terrific record in evaluating and managing mortality risks, and Life Insurance companies continue to be some of the most solid and stable companies in the Financial Services sector of the economy. The clarity with which the industry has viewed the risks posed by COVID thus far gives me hope that the industry will continue to thrive.

However, the number of people who have died as a result of the disruption of our economy and healthcare delivery system that COVID has caused as well as the possibility of a resurgence of the disease in future years does suggest that actuaries and underwriters need to continue their vigilance regarding this risk if Life Insurance is to continue to play the critical role it has in the financial and risk management plans of both individuals and corporations in the future.

If history is any guide, they will, and Life Insurance will continue to provide the financial security and stability to consumers and corporations alike that it has for over a hundred years.